Past Exhibitions

Scrimshaw

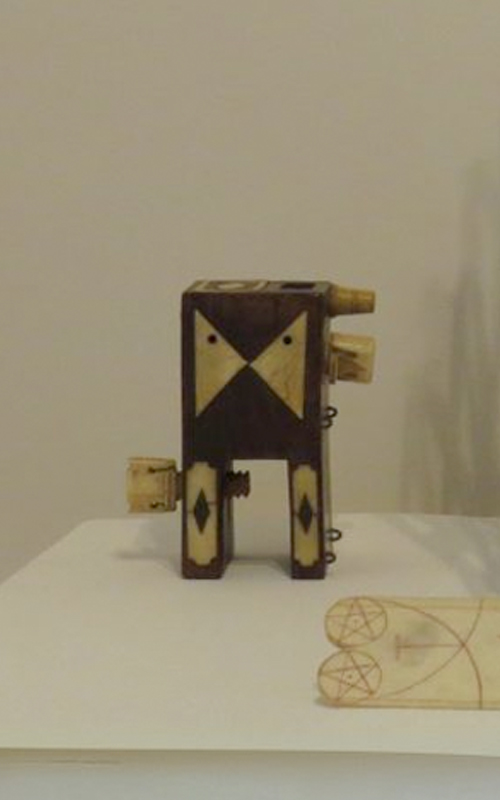

Nineteenth-century mariners on whaling voyages created some of the finest folk art found in American museum collections. Nearly every sailor on whaling ships at the height of the industry in the 1840s and 1850s became a scrimshander. The voyages were long (usually at least two years), the raw material (whalebone and whale teeth) was readily at hand, and there were long intervals with little action. Creating works of scrimshaw filled those hours and days productively for crew and captains alike.

Exhibit Items

The collection of scrimshaw at OHS is dominated by the work of one man: Captain Edwin Peter Brown (1813-1892). Born in Oysterponds, he was master of his first whaling ship by age twenty-eight, married Martha Brewer in 1843, and retired in the late 1850s to his house in Orient (directly across the street from the Candy Man). He was a successful whaling captain and proud of his achievements: on a voyage in 1843 -1844 he filled his ship with 1500 barrels of whale oil in less than a year without ever dropping anchor. On a whaling voyage on the Lucy Ann during the years 1847-1849, he was accompanied by his wife, Martha, who kept a journal of that voyage (published by OHS with the title She Went A-Whaling). Not only was Captain Brown a highly competent mariner, he was also a superb craftsman. His work is very fine, often intricate, decorative, and practical as well.

The many works of scrimshaw at OHS, made by anonymous scrimshanders as well as by Captain Brown, include examples of nearly every category of object: engraved whale’s teeth, canes, busks (corset stays), a watch stand, a miniature chest of drawers, household objects such as pie crimpers or jagging wheels, swifts (for winding wool), needle holders, pin cushions, sewing clamps, crochet hooks, tatting shuttles, and myriad other objects. To create these objects the sailors used the teeth and bones of whales, but also the walrus ivory they would have traded or bartered for on voyages to the North Pacific.

top